It’s not easy to be a good citizen in a bad society.

–Aristotle

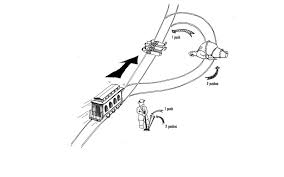

Ed and Ron start out by discussing the classic trolley thought experiment, a branch of ethics now known as Trolleyology.

An excellent book by David Edmonds, Would You Kill the Fat Man?: The Trolley Problem and What Your Answer Tells Us about Right and Wrong, along with a two-part video series on YouTube: Part I and Part II.

Why Study Ethics?

Ethics––originating from the Greek word ethos, meaning habit––is the study of morality. Morality is concerned with social practices defining right and wrong. It exists prior to the acceptance by any one individual.

In other words, morality is not a personal choice but a social construct. Ethical theory is a reflection on right actions.

After all, you would not need to study morality or ethics if you were stranded on an island, since there would be no one to be “just” or “unjust” to.

The Josephson Institute of Ethics defines ethics:

Ethics is about how we meet the challenge of doing the right thing when that will cost more than we want to pay. There are two aspects to ethics: The first involves the ability to discern right from wrong, good from evil, and propriety from impropriety. The second involves the commitment to do what is right, good and proper. Ethics entails action; it is not just a topic to mull or debate.

Normative Ethical Theory

There are many normative ethical theories. Theory is important because it enables us to control, predict or explain human behavior. Some of the most common normative ethical theories will be discussed below.

Utilitarianism

To do as one would be done by, and to love one’s neighbor as one’s self, constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality.

–J.S. Mill, Utilitarianism (Illustrated), II, 1863

Utilitarianism is one of the leading consequentialist ethical theories––that is, the morality of an act should be judged only based on its consequences.

At Glasgow University, Adam Smith’s inspiring teacher Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746) coined the phrase “The greatest happiness of the greatest number.” Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) in particular made this the cornerstone of his utilitarian philosophy as outlined in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, published in 1789.

According to Bentham, the battle in life is not between good and evil, or between reason and passion, but between pleasure and pain: “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. He proposed we weigh up the net pleasure against the net pain (what he termed “felicific calculus”).

The goal of society should be the “greatest happiness principle”––that is, “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” The concept of utility (utils), cost-benefit analysis, and the progressive income tax (e.g., an extra dollar to Bill Gates is worth less than to a homeless person), has its origins in this theory.

Some refer to utilitarians as hedonistic since they believe that any act that maximizes pleasure or happiness is right.

Kantian Ethics

Always recognize that human individuals are ends, and do not use them as means to your end.

–Immanuel Kant

Rather than analyzing the consequences of actions, another philosophical theory holds that one should do what is right. This is known as deontology, a Greek term meaning duty.

Deontologists believe in universal principles (thou shall not steal, etc.) and consequences should not be the only criteria used to judge moral behavior. The leading deontologist is the German Philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

In other words, one should do what is right, for the right reasons. If one is honest only because they believe honesty pays, it’s not as moral as those who are honest because it is the right thing to do.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue is its own reward.

–Cicero, De finibus, III, c. 50 B.C.

Greek philosophers spoke of good habits and bad habits. The good habits were called “virtues” and the bad habits “vices.” Every person develops a unique combination of both habits, known as character. This formulation allows us to predict human behavior, as is done, for instance, when we say someone acted “out of character.”

The Greeks thought that character was destiny.

Rights Theories

Rights theorists hold that human rights are independent of citizenship in a state or any other social organization, unlike legal rights that may vary from place to place. As formulated by John Locke, David Hume, and Edmund Burke––among others––natural rights consist of rights to be free from state interference.

Of course, with these rights come certain obligations, or duties, not to interfere with the rights of others. These are known as negative obligations, meaning one does not interfere with the liberty of others. Positive obligations, on the other hand, require some persons (or institutions) to provide for others (medical care, or welfare, for example).

True rights exist simultaneously among people. The exercise of a right by one person does not diminish those held by another and imposes no obligations on others.

For example, my right to free speech does not inhibit yours, nor does it oblige you to listen to my views. Furthermore, natural rights theorists believe that without freedom there is no virtue, since a coerced virtue is no virtue at all.

Other Ethical Considerations

Morality and Law

I have spent my whole life under a Communist regime, and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale than the legal one is not quite worthy of man, either.

– Alexander Solzhenitsyn, commencement address, Harvard University, 1978

The University of Pennsylvania’s motto is: Leges sine moribus vanae, “Laws apart from moral habits are empty.”

Just because a particular law is voted on by a majority does not make it moral. Apartheid, Nazism, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 were all supported by a majority. Legal remedies can sometimes preclude ethical remedies. For example, how would you be able to tell what is the right thing to do without a legal precedent?

What About “Business Ethics”?

It is common today to speak of “medical ethics,” “bio ethics,” “accounting ethics,” and so forth.

In his 1981 article in The Public Interest, “What is Business Ethics”?, management thinker Peter Drucker challenges the concept of a separate ethics for business:

What difference does it make if a certain act or behavior takes place in a “business,” in a “non-profit organization,” or outside any organization at all? The answer is clear: None at all.

…”business ethics” may be good for politics and good electioneering. But that is all. For ethics deals with the right actions of individuals.

Altogether, “business ethics” might well be called “ethical chic” rather than ethics––and indeed might be considered more a media event than philosophy or morals.

Summary and Conclusions

Character is ethics in action, it is what and who you are. Reputation is what people say you are.

Abraham Lincoln likened character to a tree and reputation to its shadow.

The Josephson Institute of Ethics lists Six Pillars of Character:

Trustworthiness

Respect

Responsibility

Fairness

Caring

Citizenship

Other books and resources mentioned

Arthur Andersen’s Website. Oscar Wilde warned: “No man is rich enough to buy back his past.”

The Rule of Nobody, the book mentioned by Ron. It’s an excellent read!

Also highly recommended in Michael Novak’s <Business as a Calling. Novak compellingly assets that business is a moral serious enterprise, and we believe he’s right.

Charles Murray’s book, Human Accomplishment, names ethics as one of the fourteen meta-inventions.

Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, Ayn Rand explains and defends natural rights.