Ed and Ron discussed the two sides of human action: rationality and irrationality on the August 22nd show, and why economists (such as Steven Landsburg, David Friedman, Steven Levitt, and many others) cling to this assumption even though it’s been challenged by behavioral economists such as Dan Ariely, Richard Thaler, and others. The assumption of rationality has come under attack in recent decades, mostly from within the economics profession itself. The idea that “Economic Man”––Homoeconomicus––has unbounded rationality, self-interest, free-will, is selfish, self-maximizing, and entirely efficient in his decisions and choices, has sometimes been proven false by a new school of economics: Behavioral Economics.

Rather than man being a completely rational calculator, similar to Mr. Spock of StarTrek fame, it seems in many areas of life we act more like Homer Simpson of TheSimpsons. It’s doubtful a Mr. Spock would need Alcoholics or Gambling Anonymous, or the idea of a self-control credit card that in advance voluntarily limits one’s spending in various categories automatically.

Mr. Spock: The Assumption of Rationality

Most of economics can be summarized in four words: “People respond to incentives.” The rest is commentary

–Steven Landsburg, The Armchair Economist: Economics & Everyday Life

Critics charge that the assumption of rationality turns the average person into a cold, calculating individual whose only interest is to maximize their wealth (or utility, or power, or whatever). Yet simple observations of human behavior reveal all sorts of activities that would not be deemed rational. We can all think of “irrational” acts that most people commit daily:

We pay higher prices for goods and services endorsed by celebrities;

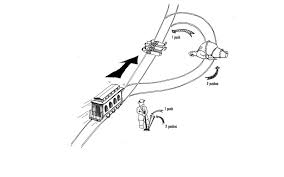

We routinely vote in elections even when we know our one vote won’t decide the outcome;

We leave tips in restaurants to strangers, in locations we will never visit again.

Given these realities, it appears as if the assumption of rationality is false, and this doesn’t seem to concern professional economists. But here is how Steven Landsburg explains this assumption in his textbook, Price Theory and Applications:

But the fact of the matter is that all assumptions made in all sciences are clearly false. Physicists, the most successful of scientists, routinely assume that the table is frictionless when called upon to model the motions of billiard balls. All scientists make simplifying assumptions about the world, because the world itself is too complicated to study.

To a large extent, the assumption of rationality is nothing more than a commitment to inquire sympathetically into people’s motives. [When we observe what at first appears to be irrational behavior] we have a choice. Either we can remark––wistfully or cynically, according to our temperament––on the inadequacy of human nature, or we can ask, “How might such behavior be serving someone’s purposes?” The first option offers the satisfaction of exempting oneself from the great mass of human folly. The second offers an opportunity to learn something.

David Friedman, in Hidden Order: The Economics of Everyday Life, explains the assumption of rationality this way:

…the assumption describes our actions, not our thoughts. If you had to understand something intellectually in order to do it, none of us would be able to walk.

Economics is based on the assumption that people have reasonably simple objectives and choose the correct means to achieve them. Both assumptions are false––but useful.

Suppose someone is rational only half the time. Since there is generally one right way of doing things and many wrong ways, the rational behavior can be predicted but the irrational cannot. If we assume he is rational, we predict his behavior correctly about half the time––far from perfect, but a lot better than nothing. If I could do that well at the racetrack I would be a very rich man.

…rationality is an assumption I make about other people. I know myself well enough to allow for the consequences of my own irrationality. But for the vast mass of my fellow humans, about whom I know very little, rationality is the best predictive assumption available.

Examples of Rationality Ed and Ron Discussed

Why do we have .99 cent pricing?

Why are Coke vending machines far more elaborate, and costly, than newspaper racks, where it’s quite easy to take more than one paper?

The four ways we can spend money.

Homer Simpson: Irrational?

Nobel Economist Herbert Simon believed that man did not maximize utility, but rather attempted to “satisfice”––that is, do good enough. He believed man had a “bounded rationality,” and often used shortcuts––hueristics––to make decisions that although not perfectly optimal were good enough.

The recent work of Behavioral Economists is fascinating, often challenging and falsifying the traditional economists’ assumption of rationality. Books such as Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions and The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic at Work and at Home, by Dan Ariely; Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein; The Mind of the Market: Compassionate Apes, Competitive Humans, and Other Tales from Evolutionary Economics, by Michael Shermer, among many others, are fascinating looks at human behavior that conclude that man certainly has the capacity in some functions to be a Mr. Spock, but that a lot of the time we are more like Homer Simpson, a Homer Economicus, if you will.

Here are just some of the anomalies that argue in favor of man’s irrationality:

Loss-Aversion Effect. We are more adverse to loss than gain of size. It takes $2 of gain to offset $1 of loss, psychologically.

Endowment Effect. We value something much more as soon as it’s ours, which is why a lot of manufacturers (and pet stores) will grant a 30-day return policy.

Confirmation Bias. Once we form a belief, or vision of the world, we pay no attention to evidence that disproves it.

Anchoring Effect. We give undue weight to anchors from the past, even if they are no longer relevant. Depression babies remember .05¢ candy bars, we recall $1.50 per gallon gas, we sometimes spend $100 for an omelet after being shown one for $1,000. Campbell’s soup sold twice as many cans when a sign on the shelf read “Limit of 12 per Person,” then when the sign read “No Limit per Person.”

Better-Than-Average Bias. We’re all above-average drivers, more rational voters than our neighbors, etc. Also known as the Lake Woebegone Effect.

Relative vs. Absolute Thinking. We tend to think in relative, not absolute terms. If you’re purchasing a $25 pen and someone in the store tells you it’s on sale for $18 at another 10 minutes away most people would leave for the other store. However, if you were buying a $455 suit and could save $448 at another store 10 minutes away, most wouldn’t bother. But it’s a $7 savings no matter what.

Zero Price Irrationality. Nothing is as exciting as “FREE!” even if we don’t need it, which is why we load up with useless knick-knacks at conventions, and spend more at Amazon.com than we otherwise planned to get the FREE shipping.

Framing Effect. How information is presented can evoke different emotions and comparisons. “The odds of survival one month after surgery are 90%” is more reassuring than the equivalent statement that “mortality within one month of surgery is 10%. Cold-cuts described as “90% fat-free” are more attractive than when they are described as “10% fat.”

Critiques of Behavioral Economics

Not all economists are convinced by the research that man is not rational, let alone willing to forego the assumption of rationality (the endowment effect and confirmation bias in action?).

Ludwig von Mises refused to call bad decision making “irrational.” He stated:

Error, inefficiency, and failure must not be confused with irrationality. He who shoots wants, as a rule, to hit the mark. If he misses, he is not ‘irrational,’ he is a poor marksman.

This is why Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, in their book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, are arguing that people need to be nudged to make the correct decisions, especially when decisions are complex and have long-term consequences, such as retirement planning.

They’ve experimented with 401(k) plans being automatically opt-in, so that employees have to fill out paperwork to opt-out. Participation rates quadrupled. They did the same with having employees pledge to increase their participation percentage as they receive future raises, which most did, compared to increasing contributions after receiving the pay raise. Since it’s easier to forgo future raises that you don’t have yet.

But as Tim Harford points out in his book, The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World, since a lot of behavioral economic theories are based on laboratory experiments––albeit very cleverly designed and executed––we can’t extrapolate from them “unless we are confident that the conditions of the experiment––which are necessarily contrived––resemble the kind of situations we face in real life.

That is far from certain, as an economics professor named John List has been discovering. On several occasions, List has taken a deeper look at the laboratory discoveries of irrationality and found that rational behavior isn’t far beneath the surface after all.”

Let the debate and research continue, since science and understanding progresses by dissent, not consensus.

Other books and resources mentioned

"That's a problem for future Homer"

Miton and Rose Friedman’s book, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement

The television series Free to Choose with Milton Friedman, with both the 1980 original series and the 1990 updated version at http://www.freetochoose.tv/

Rory Sutherland’s Zeitgeist talk, wherein he shows the $300 million effect by changing a web etailers button from “sign-in” to “continue.”

Herbert A. Simon's book, Models of My Life, where he discusses the concepts "bounded rationality" and "satisficing."